Building Health: A Physician’s View

Building Management for Occupant Health Needs to Move Beyond Comfort

SCROLL

While the appeal of profits and fear of lawyers are powerful emotions, doing the right thing to protect human health in all occupied buildings must take precedence.

Returning home an inspiring conference, "Indoor Environmental Quality Performance Approaches," in Athens, Greece, I’m struck by several serious challenges in establishing best-practice recommendations, standards, and building codes that include occupant health outcomes. We know, without a doubt, that airborne exposures affect our health, but, until recently, the primary focus has been on decreasing outdoor air pollutants. The recognition by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that transmission via indoor air is the most prominent way to spread COVID-19 was a pivotal moment. We are now tasked with managing IAQ to protect occupant health in all buildings, not just hospitals. Hence, the focus of this international conference was how to move from IAQ to IEQ to expand the role of occupant health outcomes in management of the indoor environment.

What is ASHRAE’s starting point for assessing the occupant in non-acute care hospital settings? Occupant experiences are currently addressed under the heading of “comfort,” which means 80% of occupants must be satisfied with their subjective indoor experience. Herein begins a problem. Occupant gender, age, clothing, and activity levels are all important variables that are not captured under the definition of comfort.

Thankfully, several tracts during the conference presented studies on the reliability of occupant comfort surveys to understand the full health impact of IAQ, lighting, and acoustical settings.

For example, Federrica Morandi was the first author on a report titled, “Assessing Overall Indoor Environmental Comfort and Satisfaction: Evaluation of a Questionnaire Proposal by Means of Statistical Analysis of Responses.”

One paper reported a multi-person survey on environmental parameters and the occupants’ subjective sense of comfort under the headings of thermal, visual, acoustical, air quality, and global comfort. Effectiveness of the approach was qualitatively assessed through the agreement of mean sensation/preference/comfort votes with measured indoor parameters. There was little correlation between reported subjective comfort and IAQ, including carbon dioxide levels, indicating difficulty of the occupants to discriminate or evaluate different environmental conditions. If we’re talking about health, let’s stop using the word comfort.

Our goal now is to define and manage indoor conditions that cannot be detected by our five senses. We must create a database relating the physiological impact of IAQ, light, and acoustics so that these characteristics can be properly managed.

What are the challenges associated with research on IEQ and health?

- The current surveying of occupant comfort is subjective, non-reproducible, does not represent the entire spectrum of human health, and must be understood as being limited;

- An agreement must be reached on health-related IAQ metrics;

- The privacy of health data must be protected;

- Understanding the physiological impacts of both primary IAQ constituents and secondary indoor compounds resulting from chemical reactions requires input from medical professionals;

- The abundance of data needed to understand health and exposure relationships must be properly communicated so that it is actionable rather than overwhelming;

- An infrequently discussed obstacle to monitoring IAQ to understand the occupants, especially in the U.S., where litigation is a prosperous industry, is fear of collecting data that could be discoverable in a health-related lawsuit;

- Having both health and energy metrics presents difficult choices for building owners choosing to run their HVAC in energy-saving modes rather than the potentially more expensive occupant-health modes.

FIGURE 1. The IAQ 2020 event occurred May 4-6 in Athens, Greece.

Image courtesy of ASHRAE

If these are the obstacles, how can we begin to overcome them?

- We must expand subjective occupant experiences of comfort to criteria based on objective IAQ and health data.

- Protect data that is gathered under quality-control initiatives from possible legal ramifications. Hospitals can provide guidance on this vulnerability. In 1999, the Institute of Medicine published “To Err is Human,” revealing the enormous number of hospitalized patients who were harmed from medical errors. To better understand and prevent these catastrophes, hospitals began to record the steps leading up to harmful mistakes. Unfortunately, this work quickly slowed when prosecuting lawyers in medical harm cases requested disclosure of the error logs for litigation against the hospital. To encourage hospitals to pursue safety research, The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005 was passed. This act established a network of patient safety organizations and a national patient safety database. To encourage reporting and peer review of adverse events, near misses, and dangerous conditions, it also established federal confidentiality protection from legal discovery of patient data collected as part of hospital efforts to assess and resolve patient safety issues. Hospital data collected to reduce medical errors and improve patient safety continues to be generally exempt from legal exposure. While not impenetrable to subpoenas, there is significant protection for the hospital.

- Follow clear guidelines to anonymize health data so that it is useful but does not jeopardize the privacy of individuals.

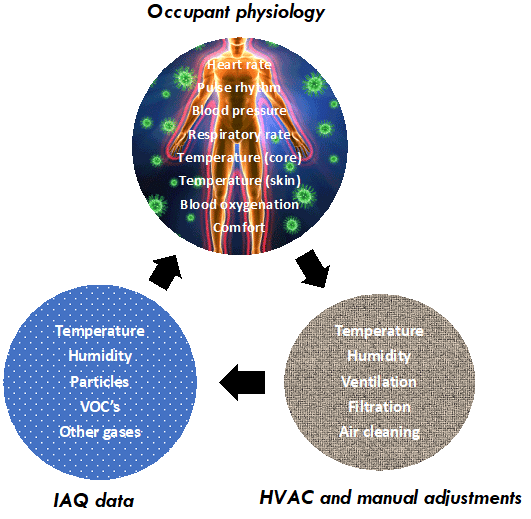

FIGURE 2. The action cycle of an indoor environment managed for occupant health, comfort, and productivity.

Image courtesy of Building4Health Inc.

We now have building and health assessment tools, which, along with computerized data analysis capabilities, can reveal the key relationships between IEQ and human health. While the appeal of profits and fear of lawyers are powerful emotions, doing the right thing to protect human health in all occupied buildings must take precedence.