REGIONAL CULTURE

By Lone Jespersen, Ph.D., John David, and Sophie Tongyu Wu, Ph.D.

Global Food Safety Culture: Asia

Food safety culture in Asia spans culturally diverse regions, but three broad types of leadership are identified in two types of companies

Image credit: DKosig/iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

SCROLL DOWN

Speakers Angel "Jun" Barnes, Jr. (Professional Service, 3M Philippines Food Safety), Dr. Ena A. Bernal (Quality and Food Safety Audit Head, Monde Nissin Corp.), and Lone Jespersen, Ph.D. (Founder and Principal, Cultivate), highlighted several unique features of Asian cultures that interplay with food safety management: evolving leadership toward modern styles, emerging risk awareness, and an immense hunger for learning.

Leadership Style

As with any geographical region, it is challenging to describe food safety culture in Asia, given that the region is so culturally diverse in leadership style, belief, practice, etc. With the aim of finding the commonalities among this diversity, three broad types of leadership were identified in two types of companies. In multinational corporations, leadership tends to be guided by clear, well-established standards and guidelines to ensure food safety and quality. In local businesses, however, vast variation exists, from family businesses sticking to a “traditional” approach to innovators adopting a “modern” leadership style. In “traditional” leadership, the family business is led by family members, people are accustomed to working in a fixed way, and new ideas are excluded or discouraged—i.e., a closed system that resists changes. For “modern” leadership, on the other hand, the local entrepreneurs possess the desire to champion the market competition. There is an evolving trend transiting from "traditional" leadership to "modern" leadership.

Leaders have a direct, active role in shaping a company's food safety culture. They must possess passion, vision, and be able to set clear goals and strategies for how to achieve such vision. In response to internal and external pressures, leadership normally takes place via a top-down pattern, for both incremental and radical changes. In fact, 73% of senior leaders change business culture because of external pressures, such as regulatory environment and customer/consumer expectations. Therefore, it is critical for leaders to maintain commitment, indicate clear direction, and enable the resources necessary to reach the destination through the change process. Speed to market is a considerable pressure to many Asian food companies. This high market competition, combined with the general trend of moving from "traditional" to "modern" leadership, demands strong business adaptability. More and more companies demonstrate food safety as a key organizational value of the company, with leaders willing to invest in improving trainings and technology. Leaders start to learn to cultivate trust within the organization by providing the resources needed, “getting out of people's way," and enabling people to do their jobs. Family businesses are motivated to accept outsiders for fresh perspectives on strategy, internal risk assessment, etc., to help leaders strengthen food safety and quality (FSQ). During this process, rapid testing and prompt communication are highlighted as critical considerations. Rapid testing, as the source of evidence, along with prompt communication, especially that targeting lab personnel, shapes the responsiveness and adaptability of a business through evidence-based, accurate, and timely decision-making on production volume, FSQ, and more. It is important to ensure purchase and continuous support for rapid testing.

With high market competition and the general trend of moving from "traditional" to "modern" leadership, strong business adaptability is extremely important. More and more companies demonstrate food safety as a key organizational value of the company, with leaders willing to invest in improving trainings and technology. Leaders start to learn to cultivate trust within the organization by providing the resources needed, enabling people to do their jobs, and "getting out of people's way." Family businesses are motivated to accept outsiders for fresh perspectives on strategy, internal risk assessment, etc., to help leaders strengthen FSQ.

Moreover, leaders are learning from third-party audits, foodborne illness outbreaks, and product recalls, through training and education among the teams. The lessons learned are then adopted internally to drive behavioral change. The hunger for learning, which will be discussed in more detail later, is viewed as a precious opportunity to change behavior. Technology and innovation are widely embraced as market advantages; leaders are willing to invest in these items in the context of food safety. Social media has effectively propagated, amplified, and circulated FSQ messages.

However, given the hierarchical leadership style and low level of challenge to authority, people usually comply without questioning, out of respect or fear. People should be encouraged to voice their opinions to verify that their input is actually helping improve FSQ.

Risk Awareness and Assessment

Risk evaluation and management enable companies to be proactive in mapping solutions and consequences, determining actions, and allocating resources, thereby enhancing organizational adaptability. Any changes in the organization will require corresponding risk identification, analysis, monitoring, mitigation, and communication. In an Asian context, the protection and creation of value (especially Asian value) are crucial in bringing proactive, risk-based thinking to life.

A study carried out in testing labs in Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam aims to develop ways to drive meaningful FSQ changes through risk management. Although initial results indicated good performance, after the first-round review, misses and laps regarding Asian value in all labs were identified and subsequently amended. The review found that they performed better with a greater level of risk awareness. All labs, as key influencers of FSQ in their organizations, demonstrated their ability to protect value. Consequently, they exceled in managing risk and achieved the highest level of accreditation after the third review. While value can foster risk awareness and effective risk management in a system, having a system can, in turn, create value for food companies. Being important players in a global market, many Asian food companies have Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) certification and are working on additional schemes, such as British Retail Consortium (BRC). It is viewed as a huge competitive advantage, and it strongly encourages the creation of value.

Awareness around the concept of risk assessment has increased in recent years. For instance, some Philippine government agencies and universities have begun to adopt and test tools for risk assessment. Many manufacturers use risk assessment for targeted improvement. Traditionally, businesses tend to rely on end-product testing, whereas an increasing number of companies today are shifting to environmental monitoring to identify high-risk areas for contamination and cross-contamination.

Hunger for Learning

The tremendous market opportunity and high level of competition not only drive the proactive, risk-based thinking on FSQ, but also open up a hunger for learning about all aspects of the food supply chain. In addition to motivation from leaders to enhance competency and capacity, there is a growing awareness among food manufacturers that FSQ must rely on everyone in the organization. Five schools of learning emerge: standards, testing, metrology, certification, and accreditation. The learning around standards—including company standards, customer standards, and regulatory standards—is the overarching pillar, affecting all other schools. Testing is based on standards and provides both critical guidance to decision-making and support to certification. Metrological ability illustrates the compliance of quality structure. Certification, although voluntary, is becoming mandatory for the industry due to customer requests. Last but not least, accreditation reflects competency based on third-party testing by certification and/or inspection bodies. Eventually, the goal is to align with expectations from the international supply chain.

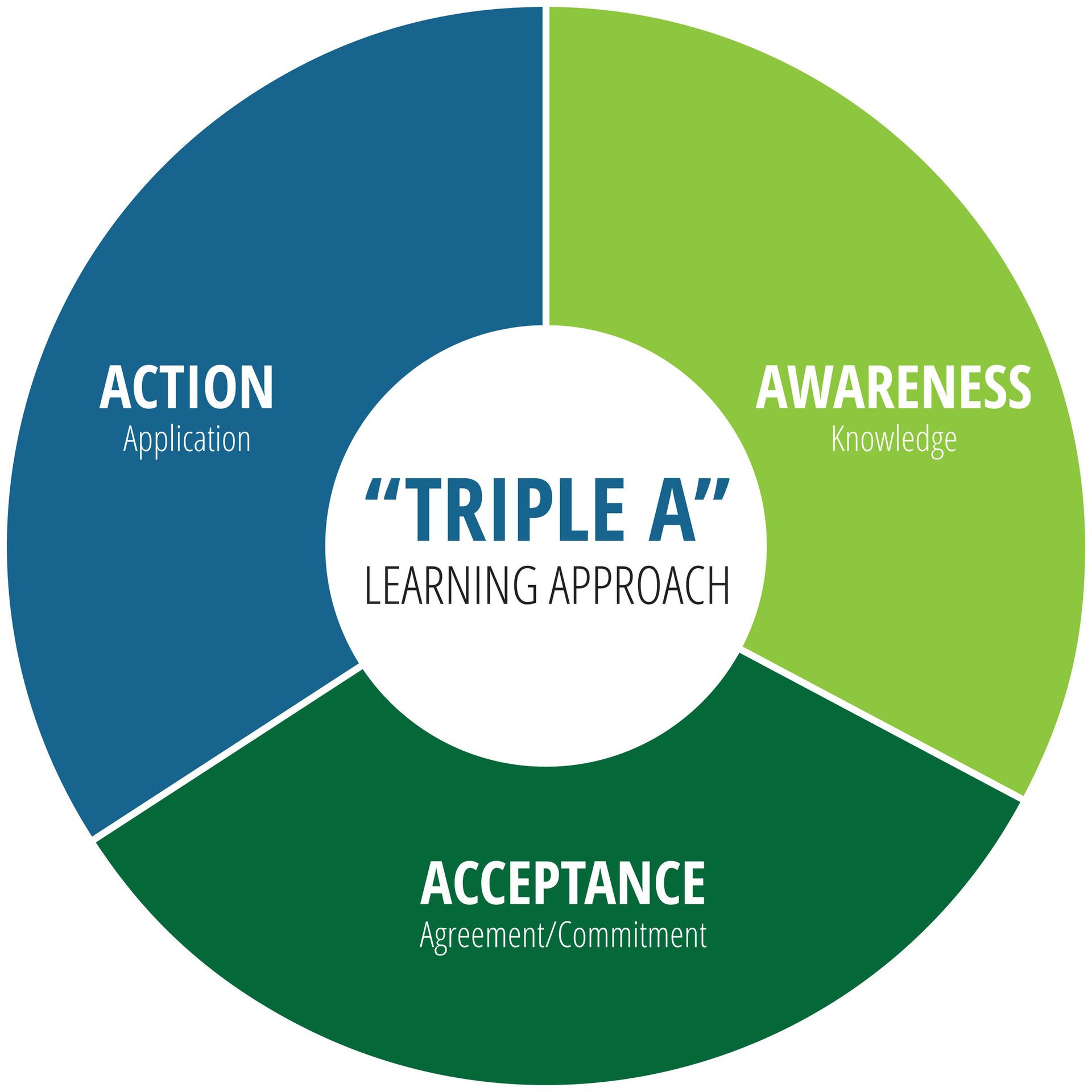

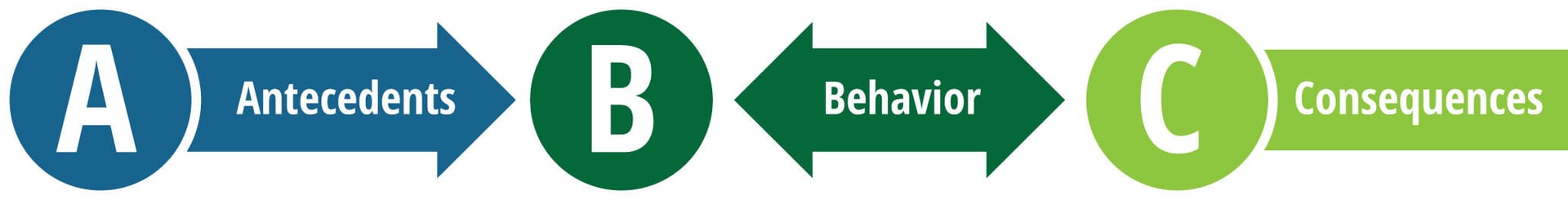

The "Triple A" learning approach is one method that bridges hunger for learning and human behavior to drive behavioral change (Figures 1 and 2). Triple A stands for awareness, acceptance, and action. Awareness lays in the basis of knowledge, commitment, and direction in and across all stakeholders. In the context of change and adaptability, it encompasses the awareness of change, requirements, and risk. Acceptance takes place when relevant requirements and information are known—people need to accept and adopt accordingly, changing knowledge to belief and value, hereby retaining the knowledge. Action ensues acceptance and is derived from the learnings; solutions are sought to increase awareness.

FIGURE 1. The Triple A Learning Approach

FIGURE 2. Turning Learning into Food Safety Behaviors; Source: Brasick, 2007

Despite the above features in driving food safety culture in Asian food businesses, several challenges exist. While learning takes place predominantly in English, many people in Asia do not speak English. People may be reluctant to ask questions, challenge authority, and ask for opinions; therefore, some issues may be left unaddressed. The turnover in the industry is staggering, and investment in training may end up having little impact. In terms of the regulatory environment, FSQ policies and standards in Asia are country-specific and not harmonized, with some countries quite weak and others very stringent; this introduces gaps and challenges to the market. To remedy these challenges, the industry is connecting with global initiatives to obtain certified tutors to better its FSQ efforts.

Lone Jespersen, Ph.D., is a principal at Cultivate, an organization dedicated to helping food manufacturers globally make safe, great-tasting food through cultural effectiveness. She has significant experience with food manufacturing, having previously spent 11 years with Maple Leaf Foods. Dr. Jespersen is also a member of the Food Safety Magazine Editorial Advisory Board.

John David is Global Scientific Marketing Manager at 3M. He holds a master's degree in molecular biology and genetics and a bachelor's degree in biological sciences, both from the University of Delaware.

Sophie Tongyu Wu, Ph.D., is a Senior Research Assistant at University of Central Lancashire and a member of Cultivate SA. She leads a food safety culture improvement project at ten UK food manufacturing companies to collect organization-wide feedback for targeted action. Dr. Wu holds a Ph.D. in food science and technology from Purdue University and a bachelor's degree in biology from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.